Route of Streight’s Raid in 1863

Streight’s Raid, Alabama

Abel Streight was born in Wheeler, New York. He moved to Cincinnati, as a young man, and by 1859 was living in Indianapolis, where he was a publisher of books and maps.

Streight was appointed colonel of the 51st Indiana Infantry regiment on December 12, 1861. His regiment was soon attached to the Union Army of the Cumberland. Streight and his regiment saw very limited action during the first two years of their service, which is said to have disappointed him greatly.

In 1863, he proposed a plan to Brig. Gen. James A. Garfield (chief of staff of the Army of the Cumberland) that he be allowed to raise a force to make to raid deeply into the South. His proposal was to disrupt of the Western & Atlantic Railroad from Chattanooga to Atlanta, which carried supplies to the Confederate Army of Tennessee. The Union Army’s commander, William S. Rosecrans, gave him permission.

Union forces from Streight’s own 51st Indiana, 73rd Indiana Infantry, 80th Illinois Infantry, and 3rd Ohio Infantry regiments were placed under Streight’s command. This force encompassed approximately 1,700 troops. The original intent was to have this force mounted suitably for fast travel and attacks; however, due largely to wartime shortages, Streight’s brigade were equipped with mules. This obvious disadvantage, combined with Streight’s own inexperience, was to prove disastrous.

Streight led this force to Nashville, departed Tuscumbia, Alabama, on April 26, 1863, and then to Eastport, Mississippi. From there he decided to push to the southeast, initially screened by another Union force commanded by Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge. On April 30, Streight’s brigade arrived at Sand Mountain, where he was intercepted by a Confederate cavalry force under Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest and harassed for several days. Streight’s force won the Battle of Day’s Gap but the battle set off a series of skirmeshes that eventually led the Union forces being surrounded and captured.[1]Streight himself was captured and taken to Libby Prison as a prisoner of war.

After ten months of incarceration, Streight and 107 other soldiers escaped from prison by tunnelling from their barracks to freedom. Eventually, Streight was able to cross through enemy territory and, on his return, gave a debriefing report to his Union commanders.

Eventually Streight was restored to active duty being placed in command of the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, IV Corps. He participated in the battles of Franklin and Nashville. Streight was given a brevet promotion to brigadier general in the volunteer army dated March 13, 1865. He resigned from the army on March 16, 1865 having achieved the rank of brevet brigadier general.

Source: Wikipedia

Go To: Civil War Heritage Trails in Alabama

______________________________________________

Georgia Secedes From the Union

Abraham Lincoln’s election in November 1860 led to the calamitous conflict known as the Civil War. Following other Southern states, delegates to Georgia’s convention to consider secession convened in its capital city of Milledgeville in January 1861. After spirited debate, delegates voted 208 to 89 to leave the Union.

Far from the war’s early fighting, and being one of the new Confederacy’s largest states, Georgia’s primary initial war contributions were its men and materials. Some 130,000 Georgians served in the Confederate military, while manufacturing facilities were quickly constructed or expanded in several cities with rail service, including Atlanta, Augusta, Columbus, Macon and Rome. The state’s relatively remote location from the conflict was ideal.

The war reached Georgia in April 1862, with the Federal capture of Fort Pulaski near its largest city and seaport, Savannah. Fort Pulaski’s surrender, caused by rifled artillery bombardment, ended the era of masonry coastal defenses.

The following day one of the war’s most storied episodes occurred through northwest Georgia. After stealing the locomotive “General” in Big Shanty (Kennesaw), the Great Locomotive Chase (a.k.a. Andrew’s Raid) covered ninety miles northward past Ringgold. Its legend prompted two future Hollywood films and a U.S. Supreme Court decision (over ownership of the General). Many of the raiders became the first recipients of the Medal of Honor. The raid itself failed, with several raiders hanged as spies.

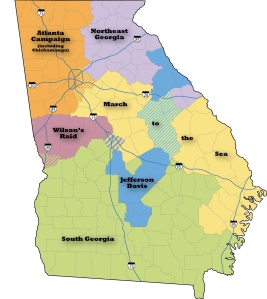

September 1863 witnessed the first major fighting in Georgia, culminating in the horrific Battle of Chickamauga. Yet 1864 was the war’s decisive year. In May a new Federal commander, William T. Sherman, began a four-month campaign to capture Atlanta. Outnumbered Confederates under Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood vainly attempted to halt Sherman’s advance. Atlanta’s fall assured President Lincoln’s re-election and ultimate Union victory.

As the war dragged on, the number of prisoners mounted. Andersonville in southwest Georgia was selected for a new stockade. Dwindling Confederate resources and overcrowding quickly became acute problems. Nearly 13,000 Federal prisoners died from malnutrition and disease. Today Andersonville honors all American prisoners-of-wars from every American conflict.

The war came to a devastating end in Georgia with Sherman’s March to the Sea in late 1864, and Wilson’s Raid in April 1865. Leaving a burning Atlanta in mid-November Sherman’s army swept across Georgia, destroying everything of possible use to the Confederacy. The indiscriminate Federal foraging resulted in their hatred by many Georgians for generations. Sherman’s march ended in mid-December with Savannah’s capture.

The following April the war’s largest cavalry campaign swept into Georgia at Columbus and elsewhere, then quickly captured Macon, again laying waste to Georgia’s war-making capacity in its wake. The next month elements of James Wilson’s cavalry captured President Jefferson Davis near Irwinville, officially bringing an end to the Confederacy.

What began in 1861 with excitement and hope ended in 1865 with 11,000+ Georgians killed, many thousands more wounded, and economic devastation. Yet nearly 500,000 African-American slaves in Georgia were emancipated, beginning their long road to full civil rights. The Civil War was Georgia’s most momentous chapter.

Go To: Georgia Trail Regions Map

_______________________________________________

The Civil War Begins

In late December 1860 speculation ran rampant as to what the newly self-declared independent Republic of South Carolina might do concerning the sixty Federal troops still garrisoned in Fort Moultrie near Charleston. Despite writing to authorities in Washington, D.C. that “The clouds are threatening, and the storm may break at any moment,” United States Army Major Robert Anderson received virtually no support from the lame-duck administration of President James Buchanan. Outdated and too large to be adequately defended by so small a force, ironically Fort Moultrie had been surrendered to the British by Anderson’s father during the Revolutionary War. Anderson did not want a repeat of history, with more South Carolina militiamen arriving daily in Charleston.

Although only 90% completed, unoccupied Fort Sumter’s isolated location on a man-made island in the middle of Charleston Harbor made it much easier to defend. Finally taking matters into his own hands, Anderson transferred his small command from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter under the cover of darkness on the evening of December 26th. This move further polarized Northern and Southern emotions, with both sides quickly viewing Fort Sumter as a symbol of their respective cause.

A haphazardly executed U.S. Navy relief expedition arrived outside Charleston Harbor on January 9, 1861, with 250 troops aboard the frigate “Star of the West.” But when the ship tried to enter the harbor and head toward Fort Sumter artillery gunners with The Citadel Military College positioned on nearby Morris Island opened fire. Fort Sumter’s guns remained silent, for fear of starting a war, and the Star of the West turned back to sea. Again emotions frayed on both sides, yet an uneasy cease-fire resumed. When the Confederate States of America, including South Carolina, officially formed on February 8th, President Buchanan’s continued indecision paralyzed any effective Federal response.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln became U.S. President, vowing in his inaugural address to defend all Federal installations. In the face of strong political opposition, Lincoln ordered a new Fort Sumter relief expedition (of supplies only) and so informed South Carolina’s Governor Francis Pickens. Alarmed Pickens quickly informed the President of the new Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, as well as Charleston’s Confederate military commander, Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. In another irony of history, Beauregard’s artillery instructor and friend while a cadet at West Point had been none other than Robert Anderson, his new adversary. Now Beauregard commanded some 6,000 militiamen and 45 artillery pieces of various sizes and quality all aimed towards his mentor inside Fort Sumter.

Meanwhile, President Davis agonized over whether to commit Beauregard to action, and thus “war.” Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs of Georgia was Davis’s only Cabinet member to oppose the use of military force against Fort Sumter. Toombs foretold that “the firing upon that fort will inaugurate a civil war greater than any the world has yet seen.” Neither Davis nor Lincoln wanted to fire “the first shot” of any conflict. But Fort Sumter’s impending resupply, and the possibility of South Carolina attacking independently if indecision continued, ultimately prompted Davis to act.